The Second Before Recognition

Every photographer is haunted by the images they didn’t take. The camera was in the bag, the light was gone too quickly, or the moment was simply too sacred to be interrupted by the click of a shutter. These unmade photographs live on in our minds, often more vivid and emotionally potent than the ones stored on our hard drives. This essay is an invitation to explore that internal gallery. It is a guide to an exercise in photographing from memory, a process of translating these lost moments from the mind’s eye back into the world, exploring the beautiful, blurry line where memory, emotion, and visual documentation intersect.

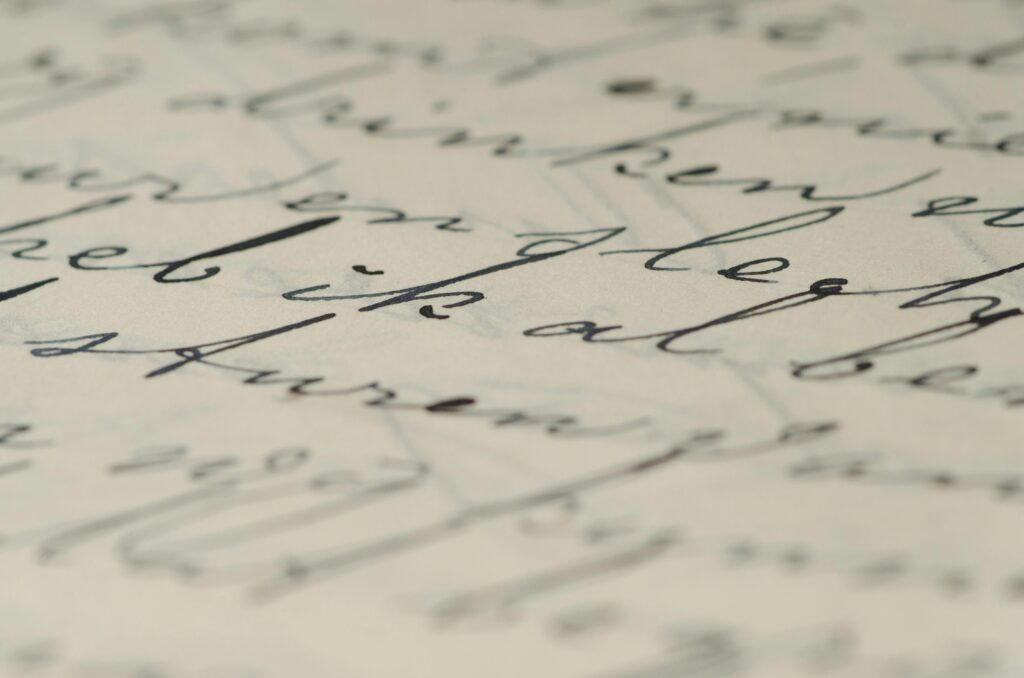

The Ghost Image: Writing it into Existence

The first step is to choose one of these “ghost images” that lingers in your memory. Before you touch a camera, pick up a pen. The task is to write the photograph into existence. Describe the scene in obsessive detail, but focus on the sensory information. What was the quality of the light? Was it the warm, thick honey of late afternoon, or the cool, blue-gray of twilight? What sounds were in the air? What was the temperature on your skin? Describe the central subject, of course, but also the periphery—the details you wouldn’t have noticed at the time but that your memory has since filled in. This act of writing is not just about recall; it is an act of excavating the emotional core of the memory.

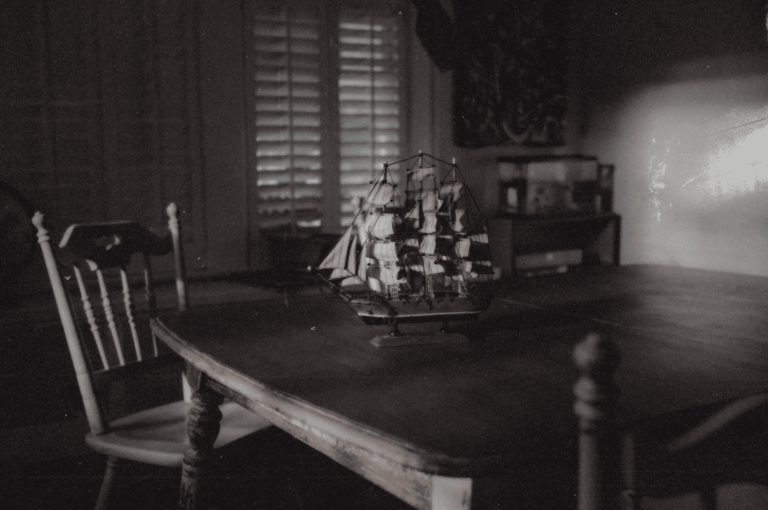

My Un-photographed Moment

For me, it is a memory of my grandfather, years ago, sitting on his porch. I remember the faded blue of his work shirt, the deep lines etched around his eyes as he looked out at the rain, and the way he held his coffee cup with both hands for warmth. I remember the rhythmic drumming of the rain on the tin roof and the smell of wet earth. I have no photograph of this, but the image in my mind is complete and saturated with a feeling of profound peace. This is the scene I will try to recreate.

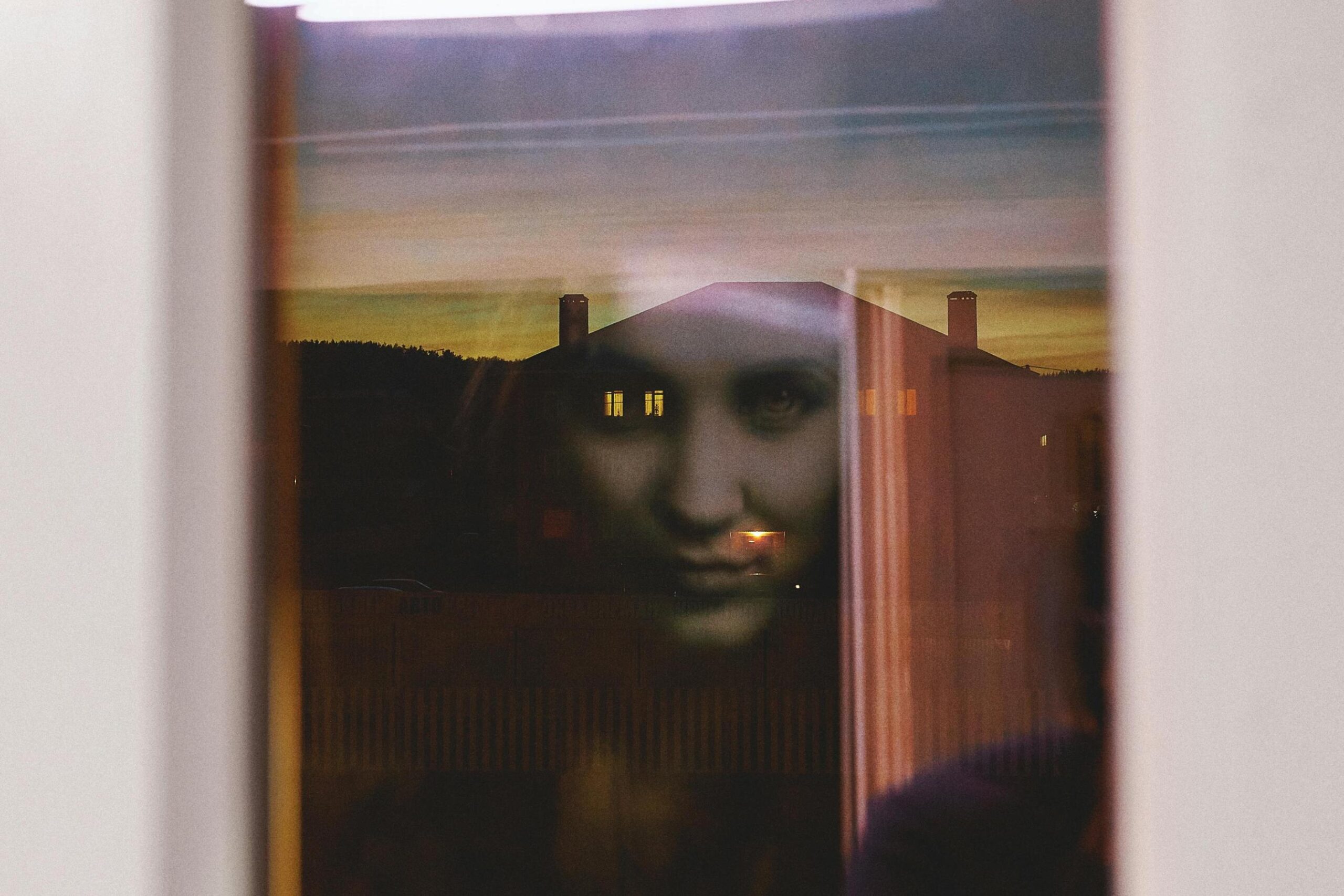

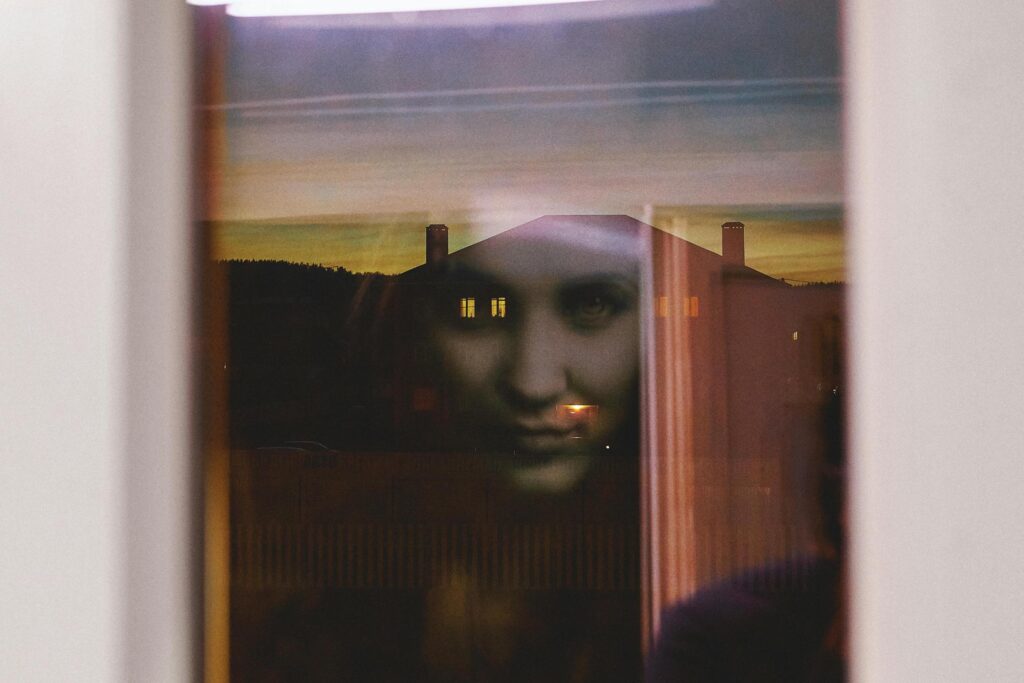

The Act of Recreation: A Collaboration with Memory

Now, with your written description as your guide, you can pick up your camera. The goal is not to create a perfect, factual replica. That is impossible. The original moment is gone. Instead, this is a collaboration with memory. The aim is to create a new image that captures the feeling of the old one. You might need to find a new subject, a new location, or wait for similar light. This process is a fascinating study in translation. How do you visually represent the feeling of safety or the sound of quiet rain? The photographic choices you make—your focal length, your aperture, your composition—become your new vocabulary. This creative process, where memory informs art, is a central theme for many artists, a topic explored by cultural institutions like The Getty through their collections and essays.

Embracing the Imperfection

The recreated image will be different. It will be an echo, a dream of the original moment. This is not a failure; it is the most beautiful part of the process. The imperfections and differences between the memory and the new photograph reveal the nature of memory itself: how it softens edges, heightens colors, and edits a scene down to its emotional essence. The new photograph is not a document of the past, but a portrait of your memory of the past. This idea of embracing imperfection and finding beauty in the incomplete, known as wabi-sabi in Japanese culture, is a deep and rewarding artistic philosophy, often discussed in journals like Kyoto Journal.

The Final Diptych: Memory and Creation

Place your written description (the first “photograph”) next to your new, physical photograph. This pairing forms a diptych that tells a powerful story. It is a story about the original moment, but also about the act of remembering. It reveals the gap between what was and what remains. This diptych honors the ghost image while giving it a new body, a new way to exist in the world. It is an acknowledgment that our most important images are not always the ones we capture with a lens, but the ones that shape us long after the moment has passed.

A Deeper Way of Seeing

This exercise does more than just salvage a lost image. It changes the way you see. It trains you to be more present in the moments you are experiencing, to notice the details that make a scene feel the way it does. It reminds you that the camera in your mind is always with you, always recording. It connects your technical skills as a photographer with your deepest emotional experiences, fostering a more holistic and meaningful creative practice. This link between mindfulness and the creative process is a rich area of exploration, one that resonates with the work of many contemplative thinkers and artists, whose ideas are often explored by platforms like On Being. Ultimately, it teaches us that every photograph is, in some way, a photograph of a memory, whether it was taken a second ago or recreated years later.

For a haunting meditation on emptiness and loss, captured through image and absence, read Photographing Absence: Documenting the Void