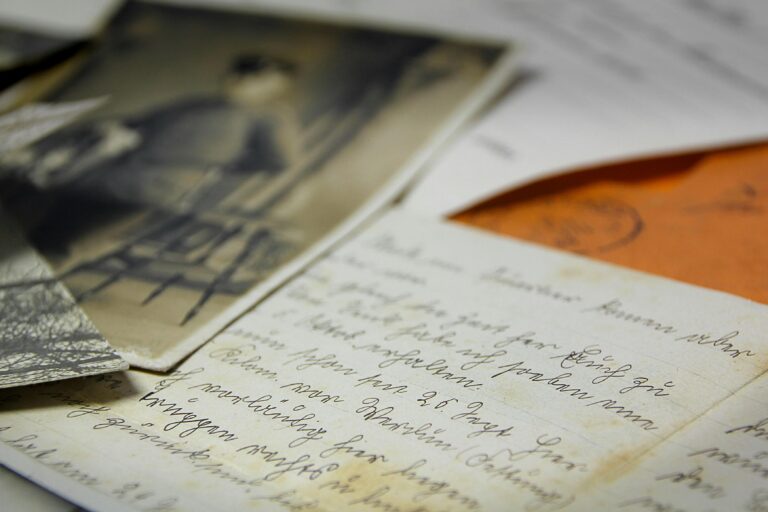

Last Harvest: Endangered Agricultural Traditions

In the quiet corners of the world, far from the vast, uniform fields of industrial agriculture, a different kind of farming persists. It is a practice rooted in memory, tradition, and a deep, personal connection to the land. This photographic essay, “Last Harvest,” is a journey into these disappearing worlds. It follows the farmers who are the last custodians of ancient cultivation methods and heritage crops, capturing the profound emotional bond between the grower and the grown, and their quiet resistance against the tide of agricultural homogenization.

A Living Library of Seeds

To hold a heritage seed is to hold a story. I spent a morning with a farmer in the Appalachian mountains who grows a rare variety of bean that his family has cultivated for over 200 years. His hands, gnarled and earth-stained, cradled the small, speckled seeds with a reverence usually reserved for precious jewels. “These beans remember the soil my great-grandmother tilled,” he told me. His farm is not just a plot of land; it is a living library of genetic memory. Each seed is a connection to his ancestors and a promise to the future. To photograph him planting these seeds is to document an act of profound cultural preservation.

The Dialogue Between Hand and Earth

The methods these farmers use are often physically demanding, relying on hand-tools and animal power rather than modern machinery. This is not a rejection of technology for its own sake, but a commitment to a different kind of relationship with the land. I photographed a woman in Peru, her back bent as she harvested a variety of quinoa using a hand-scythe. Her movements were a slow, rhythmic dance, a conversation with the earth that has been refined over centuries. This intimate, physical connection fosters a deep understanding of the soil’s health and the plant’s needs—a wisdom that cannot be gained from the seat of a tractor.

The Flavor of a Place

A heritage tomato, unlike its supermarket cousin, tastes of a specific place. It carries the unique character of its soil, the quality of its sunlight, and the history of its cultivation. These farmers are not just growing food; they are cultivating flavor. They are the guardians of a rich biodiversity that is rapidly disappearing. Photographing a farmer’s market stand filled with lumpy, gloriously imperfect, multi-colored carrots is a political act. It is a celebration of diversity in a world that increasingly demands uniformity. The vital work of preserving this biodiversity is championed by organizations like Seed Savers Exchange, who work to protect our agricultural heritage.

An Intimate Knowledge

These growers possess an intimate, almost parental knowledge of their crops. They know which plants are struggling, which are thriving, and which need extra care, not from data points, but from simple observation. I captured a portrait of a farmer gently touching the leaf of a corn stalk, his expression one of deep, concentrated listening. He was reading the plant’s story in the color of its leaves and the texture of its silk. This kind of deep, ecological knowledge, or Traditional Ecological Knowledge, is a precious resource, one that is often explored and honored in cultural institutions like the National Museum of the American Indian.

The Weight of Being the Last

There is often a quiet melancholy that hangs over these farms. Many of the farmers I met are elderly, and their children have chosen different paths. They carry the heavy knowledge that they may be the last link in a very long chain. A photograph might show a farmer looking out over their fields at dusk, a solitary figure against a vast landscape. The image is beautiful, but it is also imbued with a sense of impending loss. It is a portrait of resilience, but also of a quiet, dignified fight against time. This feeling of an era ending is a powerful theme, one that resonates in many documentary projects and artistic explorations found on platforms like Aeon.

A Harvest of Hope

Yet, this work is ultimately an act of hope. It is a belief that this knowledge, these flavors, and this biodiversity are worth saving. Every seed that is planted is an act of faith. Every harvest is a victory. To photograph this last harvest is not just to document an ending. It is to capture the enduring strength of a tradition that has nourished humanity for millennia. It is to honor the farmers who, with their hands in the dirt, are saving a piece of our collective soul. Their work is a quiet, powerful testament to the idea that the future of our food lies in the wisdom of our past.