The Ethics of Color Manipulation

A photograph is often perceived as a window to reality, a faithful record of a moment in time. But what is that reality? Is it the precise, scientific measurement of light waves that hit a sensor, or is it the feeling that the moment evoked? This is the delicate and often contentious space that photographers enter when they manipulate color. This essay is a meditation on that tension, an exploration of when altering color serves a deeper emotional honesty, and when it risks becoming a distortion of truth. It’s a conversation with photographers who navigate this line every day, seeking to convey authentic feeling in a world of editable hues.

Visual Accuracy vs. Emotional Truth

The central question is one of intent. Is the goal to produce a visually accurate document, or is it to communicate an emotional experience? A landscape photographer I spoke with, named Anya, described a sunset she shot. The camera, she explained, captured a muted, washed-out version of the sky. “The reality of what I felt,” she said, “was a sky on fire, a blazing, operatic farewell to the day. To present the flat, digital file as the ‘truth’ would have been a lie.” For her, boosting the saturation and warmth was not a distortion; it was an act of translation, bringing the final image closer to the profound emotional impact of the moment.

The Memory of a Color

Our memory of color is rarely precise. It is deeply intertwined with emotion. The blue of the ocean on a perfect summer day is remembered as bluer than it was. The gray of a city during a lonely winter feels deeper and more oppressive in our minds. When a photographer adjusts color, they are often not inventing a feeling, but rather trying to match the color that memory has already painted. This is a form of subjective truth, one that prioritizes the internal experience over the external fact. This concept of subjective reality is a cornerstone of many artistic movements, including Impressionism, where artists sought to capture the sensory effect of a scene, a style on full display at institutions like the Musée Marmottan Monet.

Where is the Line? A Question of Genre

The “ethical” line for color manipulation is not fixed; it shifts dramatically depending on the context. In photojournalism, the contract with the viewer is one of strict factual representation. A significant color shift could alter the narrative and break that trust. The standards for this are rigorously debated by organizations like the World Press Photo foundation. However, in fine art photography, the contract is entirely different. The artist is not a reporter but a poet, using the tools of photography to create a new reality or to express a personal vision. The viewer does not expect a literal document; they expect an emotional or intellectual experience.

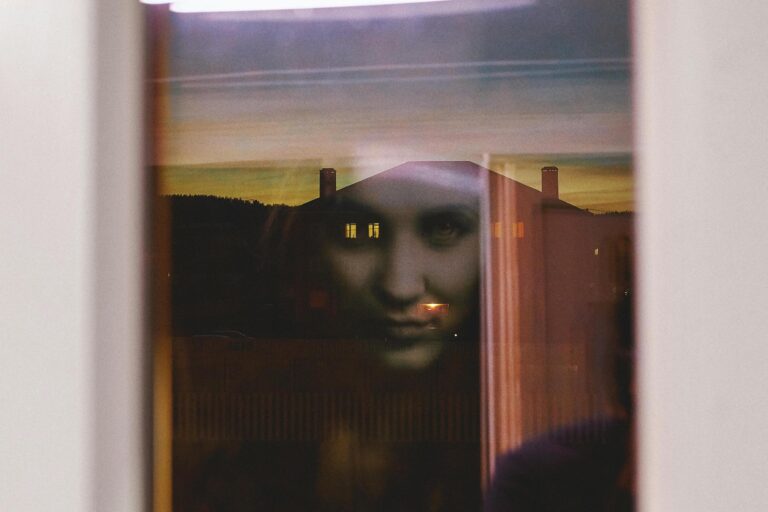

The Language of a Palette

For an artist, a color palette is a language. Desaturating an image can evoke a sense of nostalgia, memory, or melancholy. Pushing colors toward a specific hue can create a dreamlike, surreal, or unsettling atmosphere. I spoke with a portrait photographer who often uses a very muted, almost monochromatic palette. “I am not trying to show you what this person looks like,” he explained. “I am trying to show you what it felt like to be in the room with them, the quiet, introspective mood that filled the space between us.” His manipulation of color is a deliberate artistic choice, as intentional as a painter choosing their pigments. The power and psychology of color are subjects of endless fascination, thoughtfully explored by resources like The Guggenheim in their analysis of abstract art.

The Dangers of Inauthenticity

While artistic license is powerful, there is a danger. When does emotional honesty curdle into inauthentic, trend-driven aesthetics? The “orange and teal” look that dominates so much of social media is a prime example. It is often applied without consideration for the original moment, a stylistic veneer that homogenizes every experience. Here, the color manipulation is not serving an emotional truth; it is serving an algorithm. The image is no longer a personal expression but a performance of a popular look. The resulting photograph feels hollow because its emotional palette is borrowed, not felt.

A Practice of Intentionality

Navigating the ethics of color manipulation requires a practice of deep intentionality. The photographer must ask themselves: Why am I making this change? Am I trying to recapture a feeling I truly experienced? Am I attempting to communicate a specific mood or idea? Or am I simply trying to make the image “look better” according to a fleeting trend? The honest answer to that question is where the ethical path lies. The image is most powerful when the color, whether true-to-life or heavily stylized, is in service of a sincere and authentic vision. It is about ensuring that every adjustment, every shift in hue and saturation, makes the final image not just more beautiful, but more true to the heart of the story being told.

For more on capturing authentic stories through imagery, check out my article, Visible Invisibility: Portraits of Night Workers.