Fermentation as Memory: The Living History of Japanese Koji Masters

In the quiet, cedar-lined rooms of traditional Japanese workshops, time is not measured by a clock. It is measured by the slow, deliberate transformation of rice, soybeans, and salt into living foods. This is the world of fermentation, a craft where artisans partner with microorganisms to create miso, sake, and tsukemono that are not just food, but repositories of cultural memory. This photographic essay is a journey into these sacred spaces, a meditation on the patient, symbiotic relationship between the koji master and the invisible life they cultivate, and an exploration of how this ancient practice reflects a deeply philosophical approach to time.

A Dialogue with the Unseen

To watch a koji master at work is to witness a silent dialogue. The craftsperson is not an overlord, but a guide, a caretaker. I spent time in a small, family-run miso brewery where the air itself felt alive—thick with the sweet, earthy scent of fermenting soybeans. The master, an elderly man whose hands moved with a slow, practiced grace, spoke of the koji mold (Aspergillus oryzae) as his partner. His job, he explained, was simply to create the perfect conditions—the right temperature, the ideal humidity—for the microorganisms to do their work. My camera focused on his hands as he spread the steamed rice, his touch both firm and gentle, a gesture of profound respect for the unseen life he was nurturing.

The Koji Muro: A Sacred Nursery

The heart of any sake brewery or miso-ya is the koji muro, the cedar-walled room where the koji mold is propagated. Entering this room is like stepping into a sanctuary. The warmth is immediate, a humid embrace that feels ancient and vital. I photographed the shallow wooden trays, or toko, where the rice, now dusted with spores, was carefully swaddled in cloth. The master would check on it through the night, not with a timer, but by feel and smell, his senses tuned to the subtle shifts in the fermentation’s progress. This deep, sensory connection to a natural process is a form of art, a theme beautifully explored in the works displayed at cultural institutions like the Japan House London.

Patience as an Ingredient

In a world that prizes speed and efficiency, the fermentation master’s greatest tool is patience. Miso can take months, even years, to reach its peak flavor. Sake requires weeks of careful temperature control and monitoring. This is not passive waiting; it is an active, mindful observation. The process teaches a different understanding of time, one that is cyclical and organic rather than linear and rigid. A photograph might capture a row of massive wooden barrels, their surfaces dark and stained from decades of use. They are not just containers; they are vessels of accumulated time, each layer of patina a record of past vintages. This philosophical approach to time and craft is a central tenet of many Eastern philosophies, which are thoughtfully examined in publications like the Kyoto Journal.

Tsukemono: The Taste of a Season

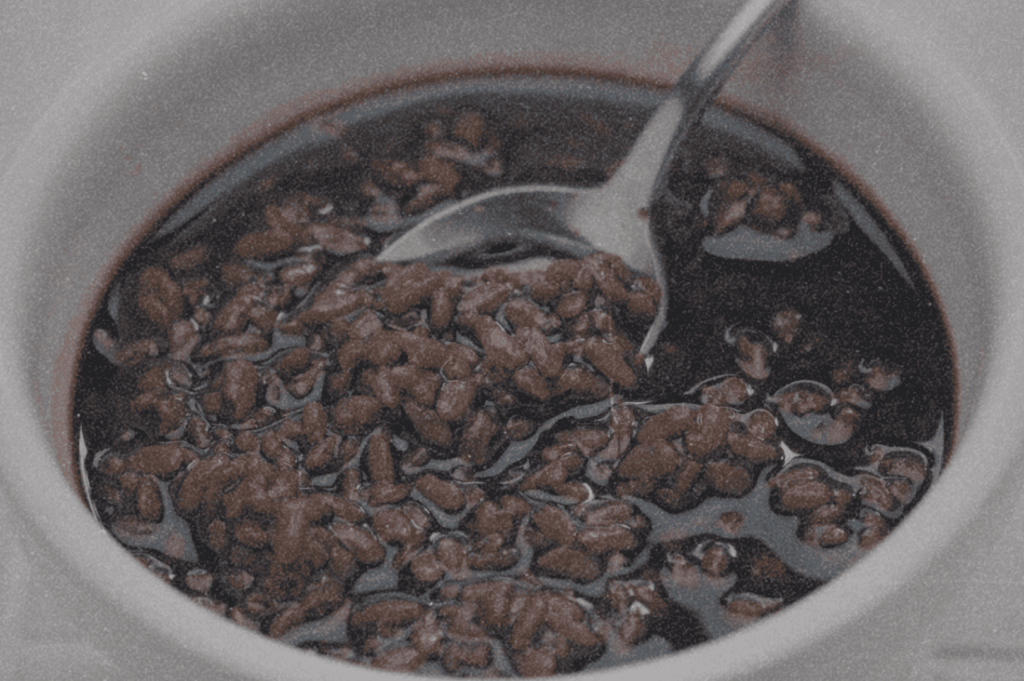

Even in the seemingly simpler world of tsukemono (pickled vegetables), this philosophy holds true. I photographed an elderly woman in her kitchen, her hands skillfully massaging salt into fresh cabbage. The resulting pickles would capture the fleeting taste of that season’s harvest, preserving it for the colder months. Her movements were not rushed. They were a ritual, a transfer of energy from her hands to the food. The finished product is more than just a condiment; it is a taste of a specific moment in time, a living memory of a past season.

The Food as a Living Archive

What these masters create is more than just sustenance. It is a living archive. The specific strain of koji used by a brewery has often been passed down for generations, a direct, unbroken lineage of flavor and tradition. When you taste a piece of traditionally made miso, you are not just tasting soybeans and salt; you are tasting the accumulated knowledge of every master who has tended to that specific fermentation. It is a form of history that you can taste, a connection to the past that is both deeply personal and culturally significant. The idea of food as a carrier of cultural identity is a powerful one, often highlighted by organizations dedicated to preserving culinary heritage, such as Slow Food International.

A Legacy of Breath

Photographing these artisans is an exercise in humility. It is a reminder that some of the most profound creations are the result of collaboration with forces far older and more patient than ourselves. The koji master does not create life; they create the space for life to flourish. Their legacy is not in a static object, but in a living, breathing process. It is a legacy carried in the aroma of fermenting rice, in the complex umami of aged miso, and in the quiet, meditative rhythm of a craft that honors the slow, transformative power of time itself.

If you’re drawn to stories of tradition and craft, you may also like The Last Spoonful: Documenting Final Meals Prepared by Aging Family Cooks and Hunger for Home: Immigrant Chefs Recreating Disappearing Regional Cuisines, both of which explore how food becomes a vessel for memory and cultural preservation.