The Grandmother’s Hands: Recipes Without Measurements

In a world governed by precision and data, there exists a form of knowledge that cannot be written down. It lives in the hands of our elders, a wisdom passed down not through recipes, but through touch, feel, and intuition. This photographic essay is a tribute to the grandmother’s hands—the ones that knead dough to “the right consistency” or add “just enough” salt without a single measuring spoon. It is a quiet observation of how traditional dishes are prepared by feel, a documentation of the tactile wisdom that flows through generations.

A Recipe Held in Muscle Memory

When I asked Elena to share her recipe for bread, she laughed. “There is no recipe,” she said, her hands already working in a large wooden bowl. Her movements were a slow, rhythmic dance. She didn’t measure the flour; she scooped it until the mound felt right. Water was added not by the cup, but in a slow stream until the dough began to come together. This is a knowledge that lives in muscle memory, a deep, cellular understanding of ingredients. The camera’s job is not to decode this process, but to honor it—to capture the grace and certainty in her hands as they fold, press, and shape the dough.

The Language of Touch and Texture

The vocabulary of these cooks is entirely tactile. “You wait until it feels like a baby’s cheek,” one woman told me, describing the perfect texture for her pasta dough. Another, making a savory stew, added spices by the pinch, her fingers sensing the exact amount needed. The knowledge is in the feeling of the dough’s resistance, the sound of a sauce as it simmers, the aroma that signals a dish is ready. These sensory cues are the measurements. Photographing this requires a focus on the intimate relationship between hand and ingredient—the way fingers test the stickiness of a batter or the tenderness of a vegetable.

The Cupped Hand as a Measure

The first measuring cup was a cupped hand. Watching these women cook is like witnessing the origin of measurement itself. A “handful” of rice, a “pinch” of herbs—these are the original, human-scale units of cooking. I photographed a grandmother, her hand cupped and filled with lentils, the lines on her palm like a topographical map. That single image holds a story of countless meals prepared, of a family nourished. It is a portrait of a living tradition held within a palm. This connection between craft, tradition, and daily life is a powerful theme, one often explored in the folk art collections of museums like the American Folk Art Museum.

Knowledge Passed Through Shared Action

This wisdom is not taught through instruction, but through shared action. A daughter or grandchild learns by standing beside their elder, their own hands mimicking the movements. They learn by doing, by feeling, and by making their own mistakes until their hands, too, begin to understand. This form of embodied learning is a powerful counterpoint to our modern, screen-based world. It’s a reminder that some of the most profound knowledge is transferred through physical presence and shared experience. The deep value of intergenerational knowledge is a subject often explored in thoughtful storytelling projects, like those curated by platforms like StoryCorps.

A Portrait of Trust

To cook without measurements is an act of trust. It is a trust in oneself, in the ingredients, and in the process. There is no anxiety, no double-checking a recipe. There is only a calm, confident flow. This is what makes the food taste the way it does; it is imbued with the cook’s own spirit and presence. The photographs aim to capture this sense of peaceful confidence—the serene focus in a pair of eyes looking down at a simmering pot, the relaxed posture of someone who has performed this ritual thousands of times. The connection between mindfulness, food, and well-being is a deep one, a topic thoughtfully explored in many contexts, including by communities like Plum Village.

More Than Just Food

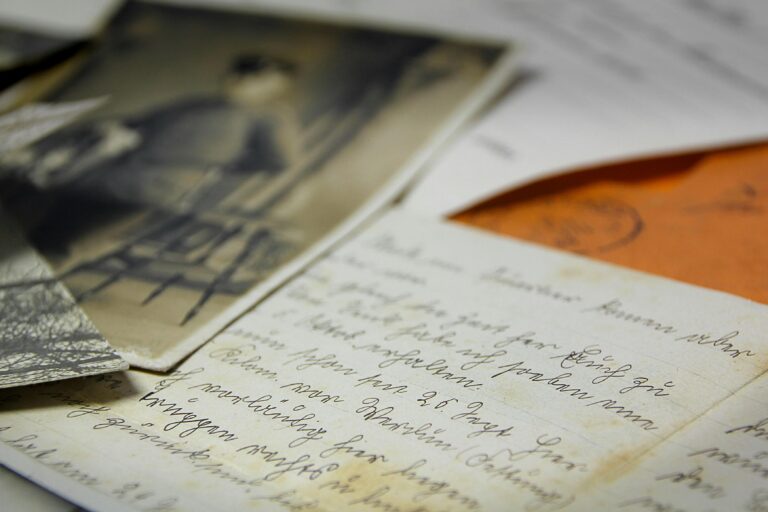

Ultimately, these dishes are more than just food. They are a tangible connection to the past, a taste of a specific family’s history and a culture’s soul. Every meal prepared by these hands is an act of remembrance, a way of keeping ancestors and traditions alive at the table. Photographing the grandmother’s hands is not just about documenting a cooking technique. It is about capturing an act of love, an act of memory, and an act of cultural preservation. It is a testament to a form of wisdom that, in its beautiful imprecision, nourishes us in a way that no measured recipe ever could. It is the warmth of a legacy served on a plate.

It is the warmth of a legacy served on a plate. This same reverence for time and tradition shapes the rhythm of seasons in Japanese washoku and endures through fermentation as memory among Japanese koji masters.